Moon Viewing

Dear Master Lexorius,

Greetings. I am Elias Mordran, student and researcher at Ishtar Academy. I have need of your assistance in a most delicate manner…

Moon Viewing was made in two weeks for the Pirate Software Jam 15. It was made with DeveloperChipmunk (a co-worker of mine), Cache31522 (my brother), and Carl_Wheezer (a friend of my brother). The Jam’s theme was “Shadows and Alchemy”.

The Jam

Having made some smaller games earlier in the year, I had often considered the idea of doing a game jam. I’m not exactly a huge fan of Pirate Software (I like the guy just don’t watch too much of his stuff)1, but was excited by the idea of participating in a large jam. Cache and Chipmunk were also familiar with his stuff, so it seemed like a natural choice for us as first-time jammers.

The Theme

At first I didn’t love this theme, “Shadows and Alchemy”. There were other themes offered that I thought were much cooler, like “Dying Planet”. I felt this one was a bit too limited, and a good game jam theme needs to be broad, maybe even have multiple meanings to work off of. But then Thor changed my mind as he spoke on how these words can be interpreted:

- “Shadows” can be more than just the absence of light, it’s also secrecy, darkness, corruption. A shadow play, a shadow government, a shadow of a doubt.

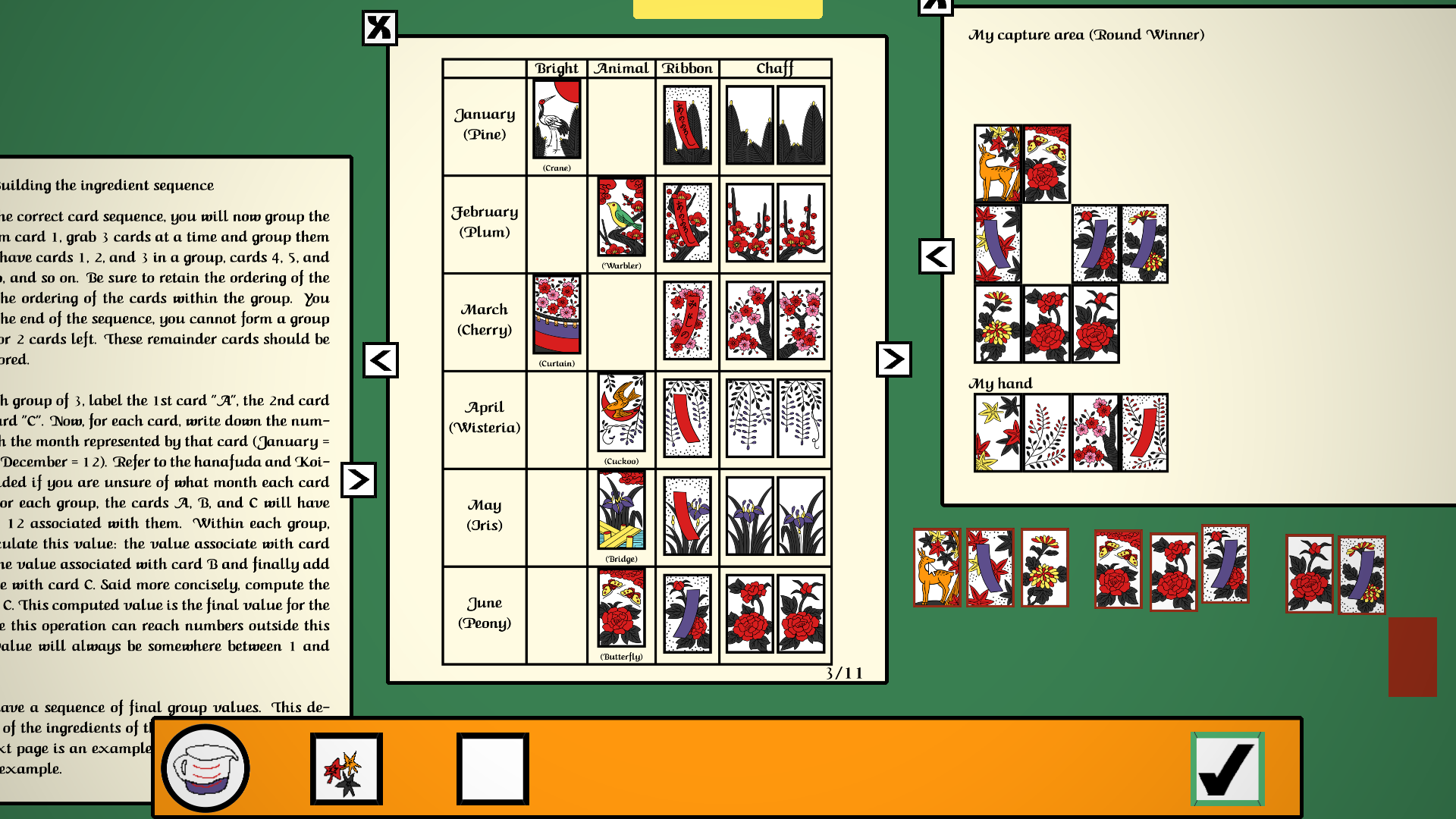

- “Alchemy” is more than just combining ingredients, it’s also transformation, transmutation, or synthesizing new materials. Think turning lead into gold. It’s also ciphers and encryption, since real-world alchemists would encode their recipes in paintings.

Chipmunk, Cache, and I chatted as the theme was announced, and we brainstormed the rest of the day. By evening, Cache and I had two strong ideas, but we went with mine.

The Plan (or lack thereof)

My idea was convoluted, complex. Dense, even. Ambitious for two weeks and four inexperienced devs. We delegated the work as we had planned, Chipmunk would do most of the programming, Cache would do the writing and some game design, Carl would do the art, and I would do all the rest, including the puzzles and solutions, music and sounds, and some additional programming.

We chose to use Godot almost instinctively. I had a blast working in it with a previous project (even though that game didn’t turn out all that well) and the rest of the team seemed to generally have positive thoughts about the engine. I am happy with our choice, Godot is excellent.

Right off the bat, we made a huge mistake. While the idea for the game existed quite solidly in my head, we didn’t take the time to properly write it down. We did not create a game design document (GDD). Not only is a GDD part of the required materials for this jam, I learned about halfway through making this game just how important having this reference would have been. We did, of course, wind up making one a couple days before the end of the jam, but it was more a description of what we made rather than a plan of what we would make.

Why did we skip this step? I chalk it up to naivety. My thought at the time was that games, as well as software as a whole, are malleable and prone to continuous change as you make them. Software should be made in an agile way, and having a design which is followed to the letter is not agile, it is the opposite of agile. But the flaw in this thinking is clear to me only after having made Moon Viewing: having no plan risks killing any project, agile or not.

Thankfully, this project was not dead in the water, despite the lack of a clear plan. It was just that the man with the plan (me) would have to delegate all the work. Oh fun.

The Work

Once I had the concept, the first steps were clear. I would begin designing the puzzles, how deciphering would work, and designing how each document would be laid out. Chipmunk would begin making a simple prototype, creating images that can be manipulated in a satisfying way. Cache would begin writing and creating a bit of lore. Carl would begin drawing the 144 ingredient sprites we required. Simple enough.

That was until Cache had to take a couple of days off for mental health reasons. Chipmunk, turns out, was only available in his down time during work and after 11:30 PM. And Carl? MIA.

But I plugged away. I wound up writing a C# script that took a CSV definition of a puzzle and generated a LaTeX document with that puzzle’s layout. These were then rendered to PNGs with ImageMagick. Why did I do it this way instead of just using Godot’s robust text system? Frankly, because I know LaTeX better and already knew how to make what I wanted to make. I used what I knew, and while it was a pain, I think it was the right choice.

Chipmunk, given the time he had, did an excellent job creating the document manipulation system. We had documents with pages that could be moved anywhere, and had protections from being pushed offscreen, plus he was working on getting the layering correct (only interacting with the topmost document).

Cache, once he was back, had some… interesting output. Despite being against the rules he attempted to use ChatGPT to generate some letters, but I told him to knock it off. What he wrote by hand was… a start. Not quite what I was looking for. He still had time to refine them though, and went to work on these with my notes.

Carl? One week in and still MIA. We had created the MVP of the game, with each puzzle in and displaying correctly and the ability to enter the solutions. And yet we had no art. A week into the jam, I had only spoken to him once, and he had nothing to show.

I did eventually sit down with him at the start of the second week, and got him to make the cover art for the game and holy shit. It’s so good.

Clearly amateur, but in a very charming way. The only thing I don’t like about is the fact that this is, quite literally, the only piece of art we got out of Carl. The 144 ingredient sprites he was tasked with making never got made, at least not by him.

I don’t wish to drag this man through the mud, however. I never got the full story here, but apparently some stuff was going down in his personal life that took time away from his work on the game. And, to quote myself speaking to Carl in a Discord message on the Sunday before the game was due: “life is more important than this game”. Carl’s absence just meant that someone else would have to draw the sprites, which of course fell to me.

Cache was also MIA by this point, but for good reasons that I won’t dive into here. This meant I also had to write all of the letters. Oh fun.

What follows is a frantic last few days of the jam. I spent Sunday drawing those ingredient sprites, a very taxing task. And holy shit. They are so bad. Like truly awful. But it didn’t matter to me, just that they were done. I went to bed early on Sunday, waking up around 2:30 AM Monday morning.

Then I spent every single free minute of my time on Monday working on the game. I created the deck system, finished the document ordering code that Chipmunk started, finalized the recipes, and updated the rest of the game’s sprites. I was up until 3 AM on Tuesday, over 24 hours awake. That was a mistake.

I took Tuesday off of work because of this, and spent the day (after waking up at 11 AM) cleaning things up. Cache was back by this point but there was nothing left for him to do as I had already rewritten everything. Chipmunk was also cleaning things up, doing some last minute fixes. I was up late Tuesday night as well, the night before the game was due.

Thankfully, Tuesday night was mostly focused on polish. One of the last things I did for the game was the sounds and, honestly, they are my favorite part of the game. The sound effects are all foley sounds, me messing with hanafuda, pieces of paper, and a wooden block. It was a ton of fun to make, and I think they came out beautifully. Then there was the music.

I don’t claim to be a particularly good musician. My Soundcloud is full of mediocre songs and bad covers. But there is something about the music I made for Moon Viewing that I just love. It’s a simple dramatic chord, I couldn’t even tell you what the chord is, but I used it everywhere. And the credits song? That same chord, just moved around a bit. In fact the credits song was mostly improvised. Had a few false starts, but it was essentially done in one take which is CRAZY. I don’t do that normally. But something about the experience of making this game… that piece just fell out of me and, while it isn’t perfect, I think it fits the game perfectly.

The End

I submitted the game at around 4 AM Wednesday morning, 5 hours before it was due. And for all that effort it was but a drop in the bucket of submissions. With around 2400 submissions, it felt incredibly daunting to see all of these other games, and a good number of them were actually decent, certainly better than our game.

Two weeks later, we receive our feedback. And with it comes a boat load of lessons.

The Lessons

-

Don’t work with people just because you know them.

Not that you shouldn’t work with people you know, just that you should consider more about people than just whether you know them or not. Consider how they work, what their schedule is, how dedicated they are to the project, what’s going on in their life. If I had known what was going on in Carl’s life, I would have kicked him out sooner. If I had known Chipmunk might have only 1 or 2 hours a day to work on the game, I would have kicked him out as well, even knowing how well he works. When it comes to projects like this, especially ones that require free time and have no certain reward, choose your company carefully.

-

Make a plan. Write it down.

Having one is better than not in almost every case. Even if the plan gets tossed out the window early on, at least you are consciously going against a plan. And writing the plan down helps delegate work, it gets the ideas out of your head, and it helps other people contribute to the plan. Without a plan, you don’t have a project. Without it written down, you don’t have a team.

-

Jam games should be fun or interesting, not impressive.

And what we built is, I would say, solely impressive. And even then, not very much so. Building a game with a 30+ minute play time with the ability to extend further is impressive, especially when the game is a complex and challenging puzzle game. But when there are 2400 submissions… who wants to play a game for 30+ minutes? No one. No one at all. Not even the judge, who from their comment seems to have not finished the game. And I don’t blame them. If I were to make this game again, I would have made it much, much shorter, maybe 4 or 5 puzzles if that. And I would have made the letters much shorter. And on that note:

-

Nobody reads.

Truly. Nobody reads your instructions. Nobody reads your lore. Nobody reads anything. This is an exaggeration, obviously, but you have to design a game with this thought in mind because, the truth is, some people don’t read. And nobody wants to read, so provide them with an option to not read and they will take it more often than not. So putting a 4 PAGE LETTER as the FIRST thing you see in Moon Viewing with a big, fat, juicy CONTINUE button right there… yeah, nobody read that opening letter. And fair enough. I wouldn’t have read it, or at least I would have gotten bored halfway through. This is by far the biggest misstep of this game, making it a game about reading.

-

So, so, so much about Godot.

I couldn’t list all the tiny little things I learned when making this game, mostly centered around Godot. But this is one of the major goals of these games, is to get to know the tools better. And Godot is a fantastic tool with so much more to learn and do.

-

Big game jams are not for me.

At least at the moment. Seeing the massive number of other submissions was, as I mentioned, intimidating. I knew going in that I would likely get very little feedback on the game, and I didn’t like that. It was “high quality” feedback from Thor (I think), but the truth is it just wasn’t very much. And likely if I had made this for a smaller jam, I would have gotten much the same feedback for this game because it has obvious problems. With a more well made, refined game, I could see this kind of feedback being useful, but at the time I had no chance of making such a game. And same thing goes as I write this: the odds of me winning or even getting top 10% in a jam this large is low. Not impossible, but low enough to discourage me from doing such a large jam for a while. Maybe once I get my skills up and find a good team, I’ll try again.

What’s Next?

Despite the troubled development, I felt so alive while making this game. The frantic rush to get something done on a timeline, the challenge of creating something so complex, and the satisfaction of finish something… it was amazing. Addicting. I wanted more. More jams, more games, more Godot. So I looked around for some jams and decided to do the September Godot Wild Jam, for which I made The Tower of Babel.

-

Correction August 14th, 2025: I no longer like the guy. He tries way too hard to be cool and refuses to change his bad opinions. That said, I still value this experience and am thankful to Thor and his community for the opportunity to make this game. ↩